A ray of hope came forward on the topic of developers and sustainability in the PAS Neighbourhood Planning event yesterday in Bristol. I was facilitating table discussions on the topic of how planners can support neighbourhood planning. I was keen to see what planners had to say about sustainability and neighbourhood plans. As it turns out, there are already examples of where communities have been vocal about their sustainability aspirations and they’ve been successful in getting developers to deliver them.

In Tewkesbury, local priorities were taken seriously by a developer who agreed to deliver a carbon exemplar project and contributed to extras like solar panels and a provision for sustainable transport. I’m going to follow up on this example for a case study so I can get all of the details behind the S106 agreement that the council used. However, one caveat that came forward straight away was that the value of the land was high enough to allow for these sustainability measures. Would the developer have been so amenable to the local priorities if that wasn’t the case?

The positive lesson was that this was a case of a developer coming in and drumming up support for a scheme and genuinely taking on board what the community wanted in return for this development. I have been quite concerned about the provision in the Localism Bill for developers to contribute financially to the production of neighbourhood plans in return for the opportunity to explicitly identify their development proposal in the plan (see reference below). I still have serious doubts that this will be a fair process in many areas. In places where the community doesn’t prioritise environmental issues we could still end up with developments that fail to make adequate provisions for adapting to the impacts of climate change or mitigating the development’s carbon footprint.

One concern on our table was that most development of the size that will be identified through neighbourhood development plans and the Community Right to Build would not be large enough to require Environmental Impact Assessments. The impact assessment gives some evidence for the chosen policy approach. It claims that objections and delays in the planning process are currently caused by communities that don’t feel as if their concerns are sufficiently represented. The proposed solution is that communities should have a greater say over what they want in their area, allowing them to “become the proponents – rather than the opponents – of appropriate growth”. Not surprisingly, the impact assessment identifies this key risk with the proposed policy option:

Neighbourhood plans are not sufficiently detailed or robust to prevent low-quality development taking place, with the result that environmental quality and economic growth are undermined.”

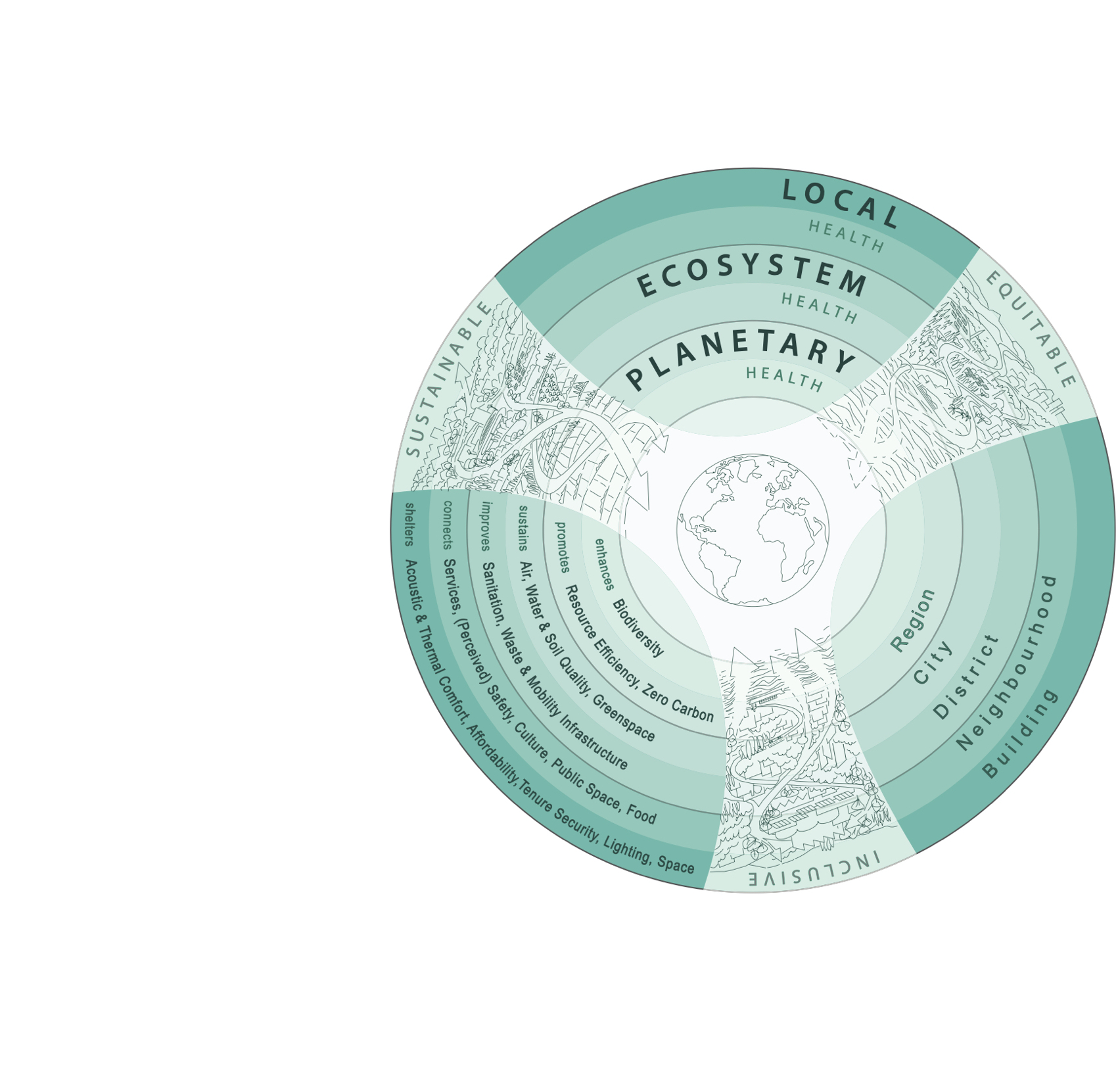

It remains to be seen how this risk will be managed in the Localism Bill. Nevertheless, the neighbourhood planning process presents clear opportunities for areas that prioritise environmental sustainability. A community could use a number of planning tools to promote sustainable design and construction or renewable energy. It’s just a question of how they’ll know what’s possible, where will they get the evidence to support their ambitions through policy, and whether they will be vocal enough to promote their plan.

Reference

Localism Bill: Neighbourhood plans and community right to build Impact Assessment, DCLG, January 2011

Note to PAS managers: I promise I didn’t abuse my facilitator responsibilities at the PAS event by talking about neighbourhood planning and sustainability the whole time!