I recently presented to a national conference of med students on the topic of planning for health. This required me to think really clearly on what the most important message was and how to get it across without using planning jargon. Using terms that resonate with health experts and providing concrete reasons to engage is what planners need to do generally to overcome the current barriers to collaboration. This ended up being a very reflective process about the role and power of the planning system. It’s fairly easy to present what planners do in theory but the practice of actually delivering things on the ground is full of challenges and sometimes disappointments. The best place to start the discussion is where planners and doctors would look first: what does the evidence say?

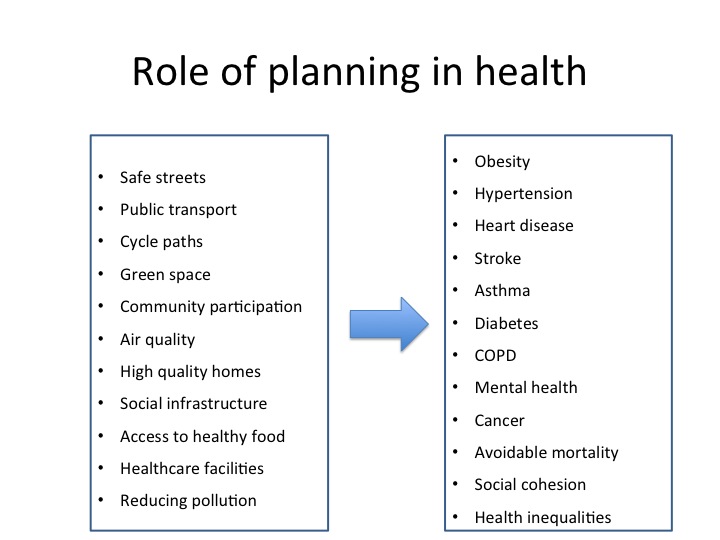

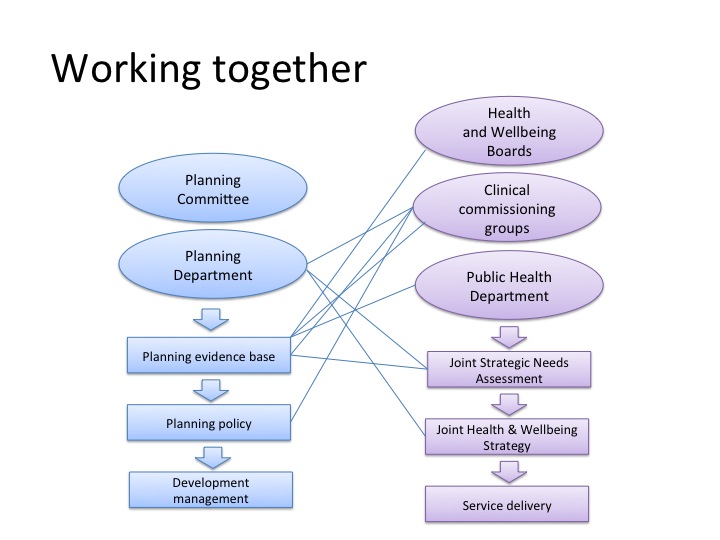

Public health professionals have a great deal of data about the health issues affecting people in a given local authority area. Some of this information is freely available on the web from sources like the Public Health Observatories. This data alone is no use unless you know which changes or improvements to the built environment will help address health issues. There is now a growing body of research demonstrating the health benefits of high quality places (including: housing, public space, transport, green space, and more). In reviewing a sampling of Joint Strategic Needs Assessments it is clear that public health professionals in local authorities have awareness of how planning can help create a health promoting environment. But the evidence that planners would need to deliver these changes on the ground goes beyond proof that a problem exists.

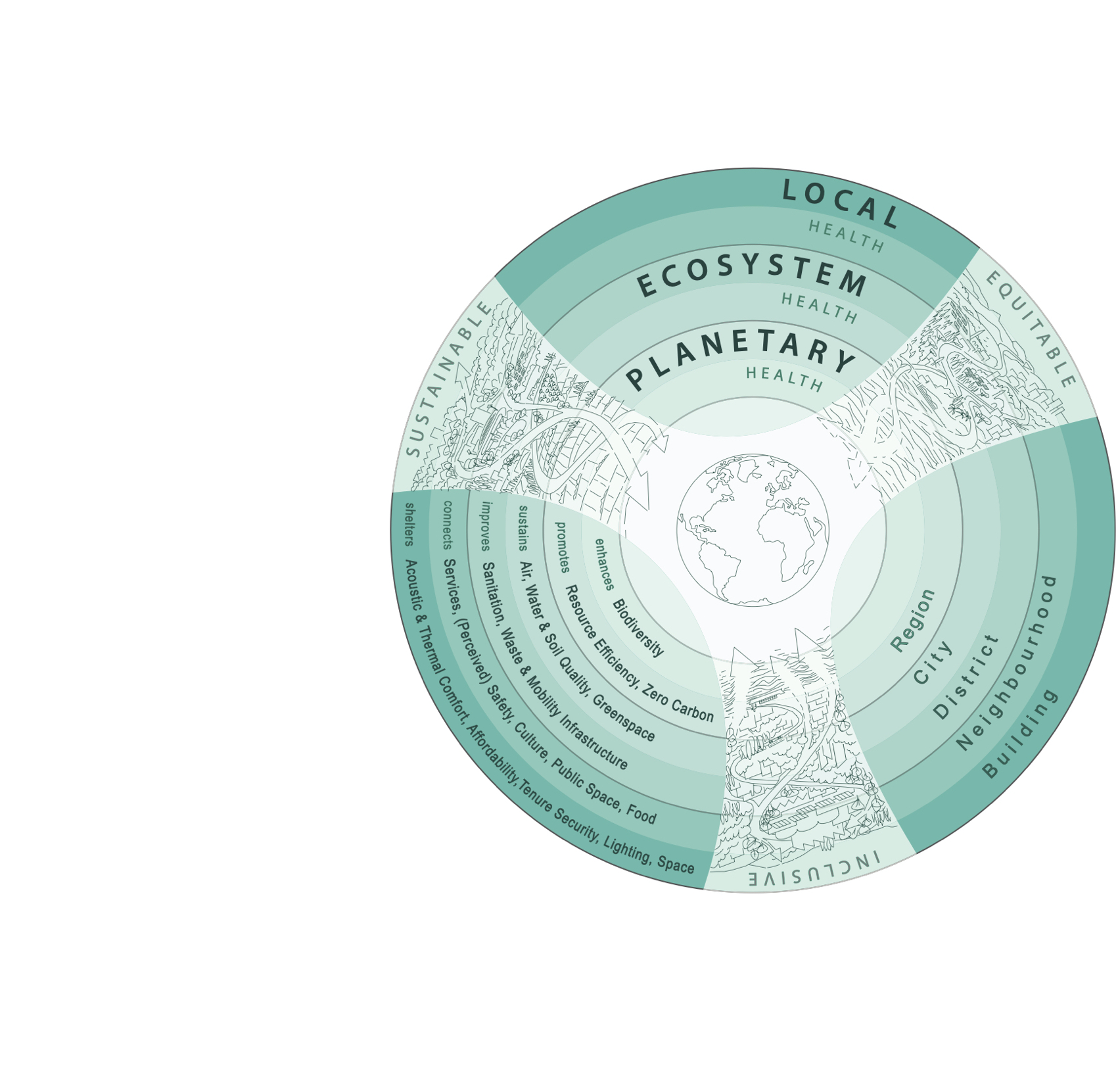

In many cases the changes required to improve health are about the wider determinants of health, which are linked to planning, including: housing; accessible/inclusive environments that promote active and social lifestyles; jobs; education; and, crime. Given the scale of new housing required in England there is significant opportunity to ensure that the homes and communities of the future will support our good health, rather than contribute to ill health. And this is where the challenge comes in. Planners know what good quality design looks like. They have the knowledge and skills to work with communities, design teams, and developers to bring about high quality homes and places. And in recent years they have had nationally available standards (such as the Code for Sustainable Homes) to ensure developers consistently follow through with agreements made before houses are built.

The Coalition government’s deregulatory approach will mean that planners cannot use some of these tools to push for high quality development. Even if they are allowed to require quality through a new set of national standards they will need to prove that it is necessary and would not affect the viability of housing developments. Furthermore, planners are having a difficult time negotiating added community benefits from developments due to viability arguments. This means that those public health professionals who until recently thought that planning could be a tool to address health needs by improving housing and the built environment will soon be disillusioned – unless we can build a financial case that proves that prioritising the short-term gains of a developer/land-owner will mean significant cost to the public purse in the medium to long-term. This could be done through the help of public health professionals who have the data and methodology to show the cost-effectiveness of specific spatial interventions.

In addition to cost evidence, planners could use evidence that shows the spatial variation of health issues across a local authority area. For example, it is useful to know where pockets of deprivation have health issues strongly associated with the wider determinants of health (see really interesting work from the University of Houston’s Community Design Resource Centre mentioned in the RTPI’s recent paper, see reference below). This information can help prioritise change and underline the argument for high quality regeneration. This is an exciting time with increasing recognition of the value of these two professions supporting each other to create healthier environments. There are challenges to overcome but there is also a growing group of specialists who understand the potential to increase wellbeing for everybody in society, not just those who can afford to live in the nicest places.

Resources:

I reviewed the Joint Strategic Needs Assessments for Knowsley, Sheffield and Hackney as a random selection of background for this blog post.

Chang, M., Ross, A. ‘Planning Health Places – report from the reuniting health with planning project’, Town and Country Planning Association, 2013

Royal Town Planning Institute, Planning Horizons No.3, ‘Promoting Healthy Cities‘, October 2014