The Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park (QEOP) is large-scale, master planned urban regeneration project on the site of the 2012 London Olympic and Paralympic Games. The vision of the project was to use the opportunity of the London 2012 Games to create a dynamic new metropolitan centre for London and an inspiring place where people want to – and can afford to – live, work and visit.

Totalling 560 acres (226 hectares), the QEOP includes plans for up to 6,800 new homes and 91,000 square metres of new commercial space around substantial green and blue infrastructure. The open space includes ‘35km of pathways and cycleways, 6.5km of waterways, over 100 hectares (ha) of land capable of designation as Metropolitan Open Land, 45ha of Biodiversity Action Plan Habitat, 4000 trees, playgrounds and a Park suitable for year-round events and sporting activities’ (1). There are five residential neighbourhoods led by different private sector partners, in addition to East Village (the former Athletes’ Village), including Chobham Manor, East Wick, Sweetwater, Marshgate Wharf and Pudding Mill.

QEOP borders four East London boroughs, Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Newham and Waltham Forest, each with high levels of deprivation and comparatively poor health outcomes. Regeneration plans in each borough aimed to transform the site’s post-industrial landscape and create better living conditions for residents. The London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC) is the official planning authority of the Olympic Park and was established in 2012 as a mayoral development corporation under the power of the Localism Act 2011. All the planning applications submitted within the boundaries of the Growth Area are processed by the LLDC instead of the local boroughs. This mechanism ensures an integrated approach to the ongoing development in a way which aims to be responsive and accountable to local concerns while reflecting the area’s strategic significance for London.

This project is featured as one of our healthy urban development case studies.

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Project type: | Mixed-use, regeneration |

| Site size: | 226 hectares (560 acres) |

| Goals: | To create ‘an inclusive community, a thriving business zone and a must-see destination where people will choose to live, work and play, and return time and time again’.(11) |

| Date started: | 2012 |

| Date completed: | Ongoing |

| Website: | https://www.queenelizabetholympicpark.co.uk/ |

| Stakeholders: | London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC); four growth boroughs (Newham, Hackney, Tower Hamlets, Waltham Forest); Greater London Authority (GLA); other public and private sector partners across the site. |

Health and wellbeing

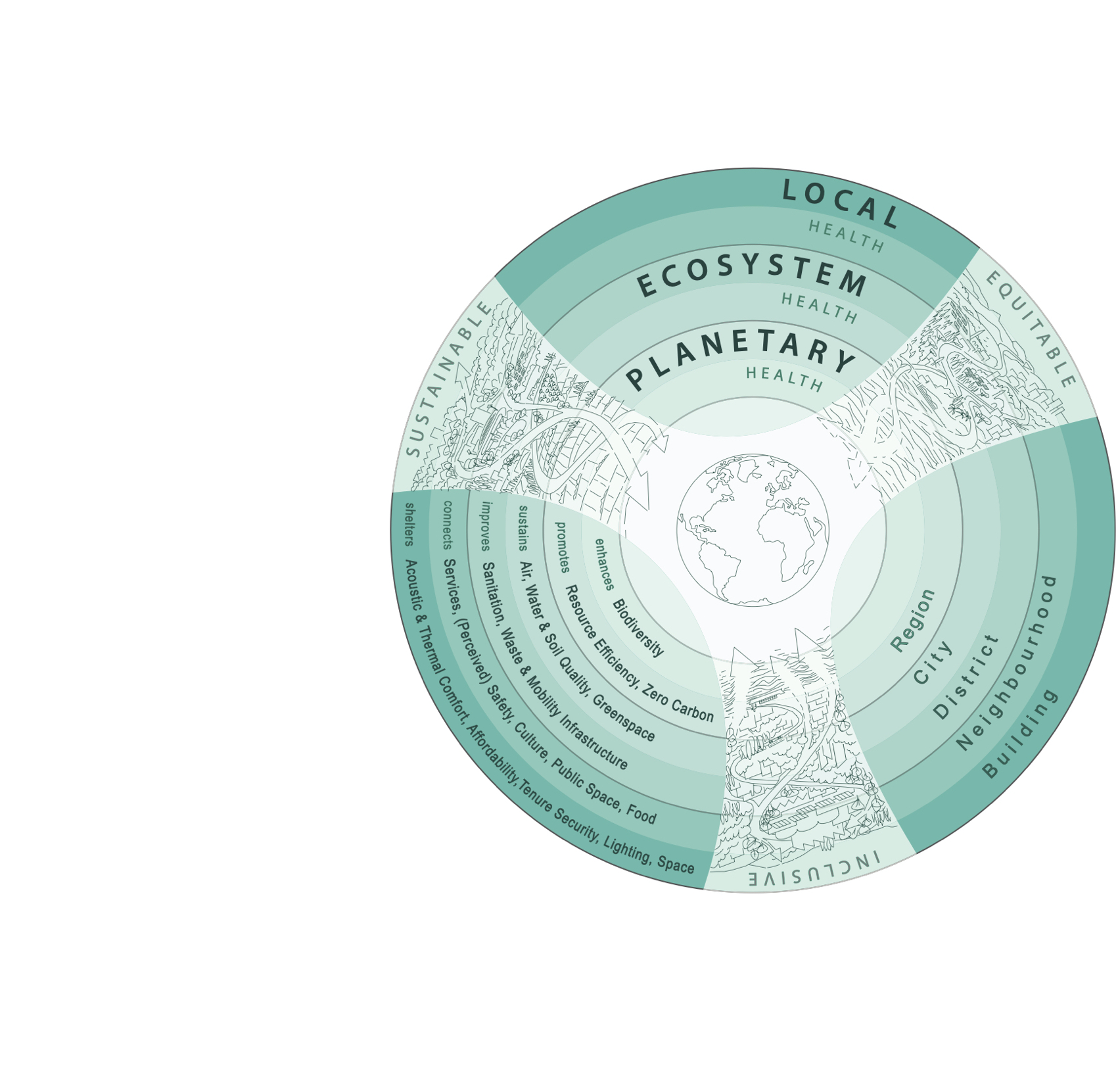

This large project includes a wide range of strategies and design features that are supportive of health and wellbeing and they cannot be adequately detailed in this short case study. In summary, health improvements of the QEOP legacy project are intentionally targeted through active design principles, incorporating nature and biodiversity into residents’ lives, walking and cycling paths across the site, public access to the sport venues, affordable and social housing (with five different tenures), proximity to transport and amenities, and integration of green paths within the residential developments. The People, Places and Performance themes in the project’s sustainability strategy also show that health and sustainability were considered in an integrated way by the LLDC (2):

- ‘People enabled to live sustainable, low carbon, resource efficient and healthy lives.

- Places that sustain parkland, waterways and walkable neighbourhoods, preparing for a changing climate.

- Performance based on sustainable procurement and long-term environmental management.’

A summary of health-related design and planning strategies adopted at QEOP is shown in the tables below, using data from published case studies (2,3).

| Planetary health | Commitment for zero carbon homes and reduction in carbon emissions across LLDC operations. Example achievements in 2020/21: 35% reduction in emissions over Building Regulations 2013 for non-residential buildings on LLDC-led developments, low carbon lighting, purchasing renewable energy. District Energy Network which provides low carbon cooling, heating and power. Commitment to use locally sourced, low environmental impact and socially responsible materials and zero waste to landfill. Example achievements in 2020/21 on the Eastwick and Sweetwater developments: 35.7% reduction in embodied carbon on building materials, 35% of aggregates in buildings, public realm and infrastructure were recycled, 99.93% of construction, demolition and excavation waste (excluding hazardous materials) was diverted from landfill. Commitment to protect and promote biodiverse habitat and wildlife through open spaces. Biodiversity Action Plans extend existing networks of green spaces, connect new and existing parks with residential communities and create new wildlife-rich parks to support climate change adaptation. The BAPs cover 45 hectares of richly biodiverse, attractive green and blue infrastructure. |

| Ecosystem health | Commitment to reduce water demand, water course pollution and local flooding. Example strategies include commitment to a potable water use of no more than 105 litres/person/day in LLDC-led housing developments, achieved through water efficient taps and appliances, water meters and mains water leak detection equipment. Rainwater harvesting and greywater treatment are also used. Commitment to facilitate sustainable modes of transport within and beyond the site. Example strategies include walking, cycling and electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Extensive soil remediation and adoption of a new ‘bioremediation’ method. Over 80% of the soil, or 1.7 million cubic meters, was reused (4). |

| Local health | The QEOP site includes a range of services (schools, health centre, retail, restaurants, sports venues, etc.) and transport facilities, meaning that residents of multiple life stages can work, study and enjoy leisure activities on site or easily travel to other parts of London. There are ample open spaces and playgrounds with equipment to promote play for all ages. Employment was a key service whereby more than 11,000 people have worked on QEOP since the end of the Olympic Games, including over 200 young apprentices; more than 25% of the construction workforce was recruited from the neighbouring boroughs; long-term operational jobs are going predominantly to local residents (6). Active design has been applied across multiple scales at QEOP (7), examples include: installation of appropriate infrastructure and urban furniture (Trim-trail fitness equipment), running activity events in the Park (Motivate East), connected walking and cycling routes and proximity of transport hubs and services. |

| Inclusion | The Inclusive Design Standards adopted by the Olympic Delivery Authority in 2007 were updated and extended by the LLDC in 2013 and 2019 (8,9). The Standards provide guidelines for all development on the park, with varying levels of scrutiny depending on whether the activity is led by LLDC. An independent Built Environment Access Panel (BEAP) reviews all development proposals. The 2019 IDS covers four topic areas: Achieving inclusive neighbourhoods, Movement, Residential developments and Public buildings. Participatory processes in the early stages of the development in 2010-12 involved consultation with local communities. More than 180,000 local people participated in community engagement activities and over 10,000 volunteering hours have been delivered on the Park (6). |

| Equity | The Equality and Inclusion Policy (10) restates an aspiration from the original bid to host the Games which was ‘to deliver new opportunities for some of the poorest and most socially excluded neighbourhoods in the capital’. The Policy’s objectives are to embed high inclusive design standards, use procurement to create opportunities for East London communities, set a standard through the LLDC’s practices for inclusion and diversity, promote disability sport and foster cohesion and integration between QEOP residents and neighbours. The policy includes specific plans for equality and inclusion, such as Women into Construction and payment of the London Living Wage. The Inclusive Design Standards refer frequently to ‘equity of experience’ of different people using buildings and the wider site.(8,9) |

| Sustainability | Sustainability is a core element of the Olympic Park’s regeneration and is summarised in seven environmental themes (2): Water management and conservation, Energy conservation and carbon reduction, Material selection, Waste management, Transport and connectivity, Biodiversity and open space, and Facilitating sustainable lifestyle. See Planetary and Ecosystem Health above. Sustainability standards were applied, such as achievement of Code for Sustainable Homes Level 4 (minimum) for all new homes. The standard includes health-related requirements, for example covering daylighting and sound insulation. |

Lessons learned

By many metrics, the health-related achievements on QEOP are vast in terms of creating new housing, jobs and leisure amenities, alongside the sustainability benefits of well-maintained green and blue infrastructure in a large city. However, there have been criticism of the regeneration project’s legacy, particularly for low-income communities. The initially proposed number of affordable housing units were reduced in the early 2010s, due to reduced government grant funding and other financial pressures.(12,13) Tensions have been reported between tenants from social housing and those in privately rented or owner-occupier housing, such as conflict over access to communal courtyards.

The paradox of both positive and problematic outcomes at QEOP is described through a photo-series of East Village, the former Athlete’s Village, depicting residents in their homes and the wider environment.(14) The author, Debbie Humphry, invited residents to choose places that were meaningful to them and thus the images show a young family in a playground, a couple with bicycles on a cycling track, people in their homes and other everyday representations of life. The narrative highlights some of the challenges that individuals experienced with accessibility and equity, such as a woman in a mobility scooter who could not open a door in her apartment block, which is at odds with the Inclusive Design Standards. Humphry writes ‘As the various perspectives across the image-set disrupt each other, a simple celebration or a straightforward critique is therefore undermined. There are echoes and repetitions throughout, but overall the ambiguities and absences provide no definitive answers and instead raise questions.’

As development is ongoing on the QEOP site, it would be premature to evaluate impact for many health and wellbeing measures.(15) An initial study found limited evidence of health and wellbeing impacts arising from the games and the regeneration (16), although the newly developed residential neighbourhoods were objectively better for physical activity for new residents than their previous neighbourhoods (17). Further evaluation would usefully establish the health benefits and disbenefits of design strategies on the site, particularly whether inclusion and equity goals have been delivered in practice.

A video of the project gives a sense of the scale of this site:

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park from the air (YouTube)

More information

- LLDC, 2013. Legacy Communities Scheme: Biodiversity Action Plan 2014-2019.

- LLDC, 2012. Your Sustainability Guide to Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park 2030.

- LLDC, n.d. Your Park, Our Planet: London Legacy Development Corporation Environmental Sustainability Report 2020/21.

- Pineo, H., 2015. UK Leading Capabilities on Sustainable Urbanisation: Final report to UK Trade & Investment. Building Research Establishment, Watford, UK.

- Pineo, H., 2020. Towards healthy urbanism: inclusive, equitable and sustainable (THRIVES) – an urban design and planning framework from theory to praxis. Cities Health 0, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1769527

- LLDC, 2016. Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park and The Surrounding Area: Five Year Strategy 2015-2020.

- Sport England, 2015. Active Design: Planning for health and wellbeing through sport and physical activity. Sport England, London, UK.

- LLDC, 2013. Inclusive Design Standards.

- LLDC, 2019. Inclusive Design Standards.

- LLDC, 2012. Equality and Inclusion Policy.

- https://www.queenelizabetholympicpark.co.uk/our-story/who-we-are

- Bernstock, P., 2013. Tensions and contradictions in London’s inclusive housing legacy. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 5, 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2013.847839

- Cohen, P., Watt, P. (Eds.), 2017. London 2012 and the Post-Olympics City: A Hollow Legacy?, 1st ed. 2017. ed. Palgrave Macmillan UK, London.

- Humphry, D., 2017. ‘The Best New Place to Live’? Visual Research with Residents in East Village and E20, in: Cohen, P., Watt, P. (Eds.), London 2012 and the Post-Olympics City: A Hollow Legacy? Palgrave Macmillan UK, London, pp. 179–204. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-48947-0_6

- Pineo, H., 2019. Increasing physical activity and equity in urban regeneration. Lancet Public Health 4, e367–e368. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30127-6

- Cummins, S., Clark, C., Lewis, D., Smith, N., Thompson, C., Smuk, M., Stansfeld, S., Taylor, S., Fahy, A., Greenhalgh, T., Eldridge, S., 2018. The effects of the London 2012 Olympics and related urban regeneration on physical and mental health: the ORiEL mixed-methods evaluation of a natural experiment. Public Health Res. 6, 1–248. https://doi.org/10.3310/phr06120

- Nightingale, C.M., Limb, E.S., Ram, B., Shankar, A., Clary, C., Lewis, D., Cummins, S., Procter, D., Cooper, A.R., Page, A.S., Ellaway, A., Giles-Corti, B., Whincup, P.H., Rudnicka, A.R., Cook, D.G., Owen, C.G., 2019. The effect of moving to East Village, the former London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games Athletes’ Village, on physical activity and adiposity (ENABLE London): a cohort study. Lancet Public Health 4, e421–e430. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30133-1