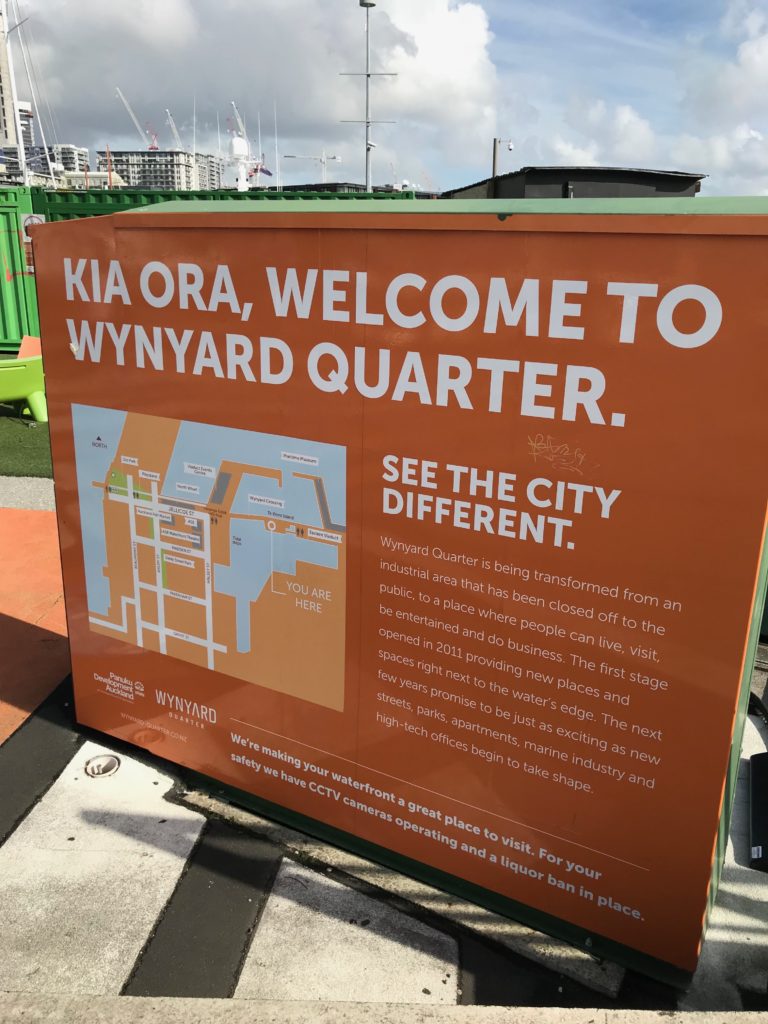

Given the long timespans of urban regeneration projects – spanning decades from initial plans to completion – I happened upon New Zealand’s largest renewal project at just the right time. Wynyard Quarter is well along its transformational journey from an industrial port into a very liveable and sustainable community.

In April 2018 it was already clear that Auckland’s planners have used fantastic public realm design and amenities to turn the port into a welcoming, walkable and fun neighbourhood. Having visited or worked on some of the world’s leading portside developments in Sweden, Hammarby, BO01 and Masthusen, I can see that this project will likely become a case study in sustainable design and development.

Walking from Auckland’s CBD you’re drawn west, past the ferry terminal and under the New Zealand’s Team America’s Cup Yacht at the Maritime Museum. You enter Wynyard Quarter by passing rows of luxury yachts and crossing a pedestrian drawbridge. As you approach, there are meanwhile uses, pocket parks and information boards drawing attention to the redevelopment. There will be 500 homes and 48,000 sq meters of commercial space in the central area of the quarter, much of which is starting to take shape now.

Visiting with my young family, we walked straight past the lovely waterside bars and restaurants to Silo Park. There is something here for all ages. A water feature, basketball net, and ‘under the sea’ themed playground were being enjoyed by children, teenagers and adults. Posters advertised outdoor concerts and an open-air cinema project against one of the silos. My favourite part was walking up the gantry, a bridge-like structure with multiple levels and partly covered in plants. It offered fantastic views of the emerging neighbourhood and the harbour bridge beyond.

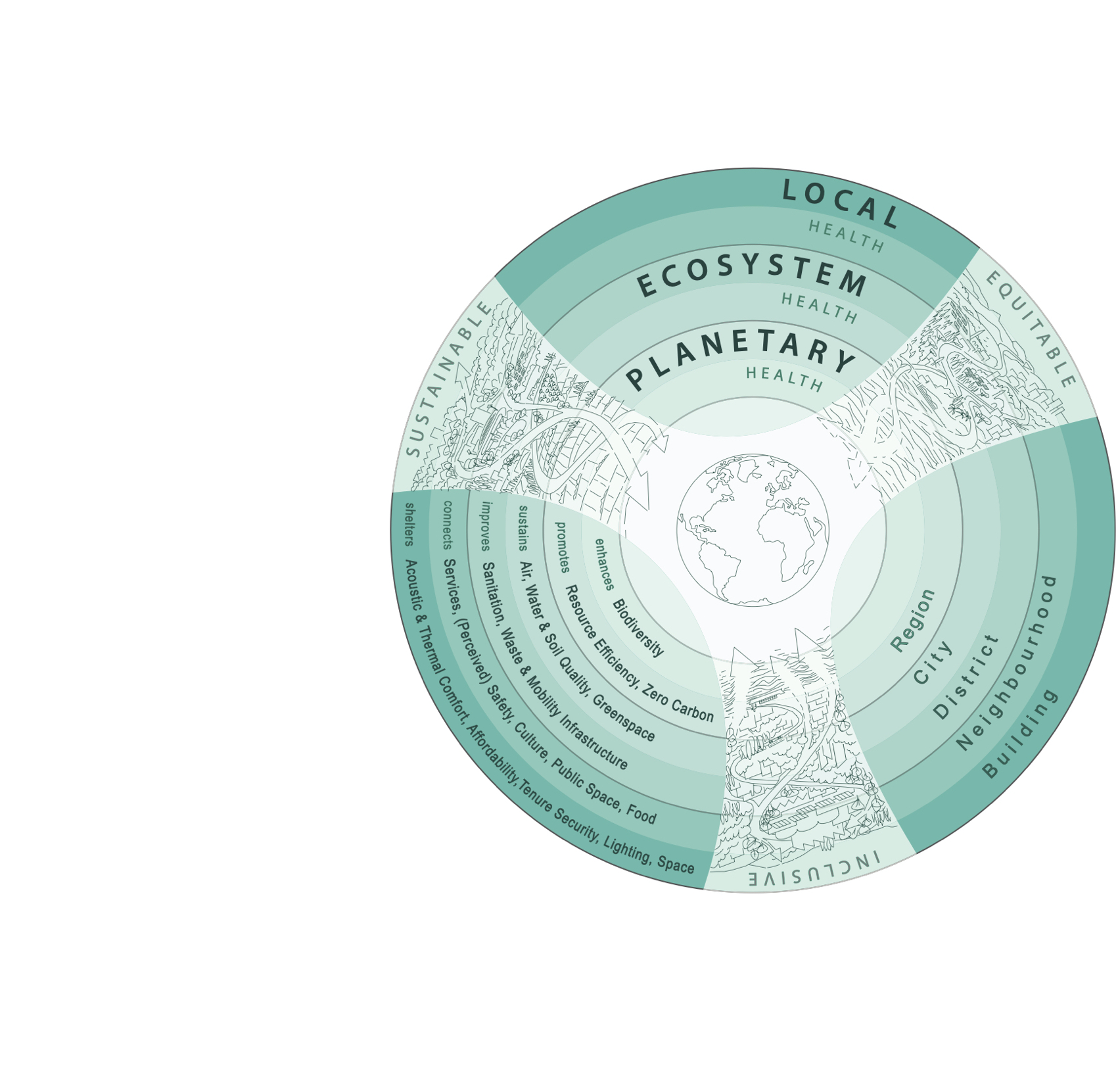

There are many planning frameworks setting out the ambitions and development requirements for Wynyard Quarter on the Panaku Development Auckland website. The project’s Sustainable Development Framework aims to move beyond zero net energy, water and waste impacts to a built environment that positively contributes energy and water and is ‘restorative’. Among other requirements, homes have a minimum target of 7 Homestar rating1 while commercial buildings will need to reach 5 Green Star rating2.

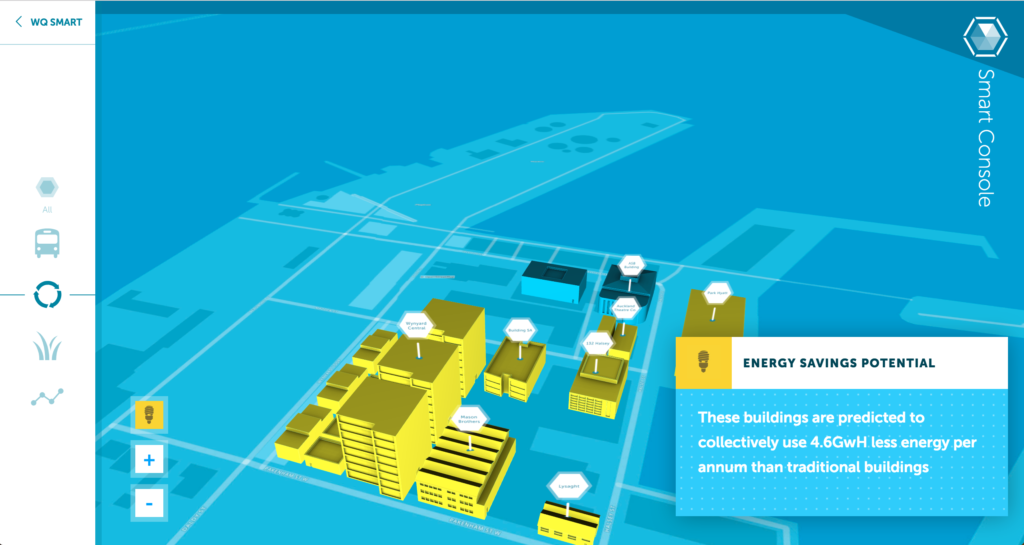

The city wants Wynyard Quarter to be a place where residents are proud of their contribution to a ‘more sustainable future’. This project has the most sophisticated monitoring system that I’ve ever seen for a masterplanning project to showcase its progress against sustainability goals, called Wynyard Quarter Smart.

Users of this online interactive tool can view information on a map of the neighbourhood or through navigating different theme areas, such as ‘Transport, Movement & Connectivity’. It’s fantastic to see that the project managers are reporting their progress throughout the renewal project.

This regeneration project is leading practice in many areas, incorporating smart systems and adopting ambitious goals for sustainability and health. Just reporting what I saw on my brief visit, here are some of the outstanding design and planning features that will support the developments’ goals for generations to come:

- Infrastructure first: The housing development is just beginning but even early residents will be able to adopt healthy and sustainable behaviours such as walking or cycling because the street infrastructure is already in place to support this. There are also plenty of things to do in the area so that people will have reasons to interact and develop a sense of community.

- Public realm design for all ages: People of all ages and abilities will find the parks and amenities around Silo Park to be fun and accessible. The gantry structure has a lift and stairs so wheelchair users or parents with buggies can see the outstanding views from the top deck.

- Safe streets: The crossing points are clearly marked and level. The pavements are wide and allow plenty of space for pedestrians and cyclists.

- Sustainable drainage: The sustainable drainage systems contribute to the landscape aesthetic and filters water.

- Identity – marine and industrial heritage: This place has a very strong sense of identity that comes across through the design of the public realm – buoys floating in grass, the gantry, the ‘under the sea’ playground, the remnants of train tracks, and of course the silos.

Wynyard Quarter is a great place to visit, live or work. If you’re planning a similar project in your city, it would be well worth exploring their approach to sustainability and the incorporation of health and social wellbeing principles. It has already won an ‘Excellence on the Waterfront’ award in the Comprehensive Plans category in the USA.

- New Zealand Green Building Council’s standard for sustainable healthy homes, https://www.nzgbc.org.nz/homestar

- Green Building Council Australia’s standard for sustainable buildings, https://new.gbca.org.au/green-star/