The long awaited Housing Standards Review Consultation was published today and we are none the wiser as to how government will achieve its aims without compromising the quality of new housing in the UK. The consultation showed:

- government’s continued tension between the localism agenda and the need to set (slash) policy at a national level to provide certainty to developers;

- a lack of consideration for new homebuyers/occupants and the costs they will pay if standards are removed;

- potential additional burdens for local plan preparation; and

- a risk that our ability to achieve sustainable development will be significantly compromised.

Localism versus centralism

The main dilemma is whether to have a national set of standards (para. 13) or to incorporate everything into Building Regulations (para. 24). In using the national standards, local authorities would need to assess viability. And they would not be able to set any additional standards to those set out in the nationally described set. The national set of standards is supposed to allow for local variation through application (i.e. you can’t apply it unless you have a really good reason). This plays to the localism agenda. The Building Regulations approach is supposed to be the centralised option that reduces uncertainty for developers by providing consistency across all local authorities.

The consultation document struggles with this tension. For example, in the security section there are two proposed standards (a baseline and an enhanced standard), both of which could be applied through local policy. Or the two standards could be ‘optional regulated options’ through Building Regulations or just the baseline standard could be set in Building Regulations (with the enhanced standard applied through local policy). DCLG are so afraid of causing a burden on developers that they invent ‘optional regulated options’ as a way of overcoming the need to require something centrally whilst still managing to be seen to be addressing the issue in some way. The irony is that this borderline policy doesn’t achieve their aim of giving certainty to developers if each standard or ‘optional regulated option’ has to be applied and justified locally.

Lack of consideration for new homebuyers and occupants

This is one of the biggest areas that this government is failing in regards to planning policy. The focus is overwhelmingly on the interests of the developer and whether requirements set by central or local government will result in developments being unviable. Government needs to start accounting for the long-term implications of catering to the development industry. In the UK, housebuilders build and sell properties with no interest in the long-term value of the asset and how it performs over time. This can result in homes that are lacking in design quality and sustainability.

Throughout the consultation document DCLG shares its view that market forces should be able to regulate the quality of housing. One example is the proposal to address the widely discussed topic of internal space standards for homes. The government’s idea is that a label is developed by industry to allow homebuyers to compare how much space new properties provide. Will this work in the UK housing market where first time homeowners are struggling to get into the housing market? What purchasing power do they have? Only wealthy homeowners would be able to choose larger properties meaning that only luxury accommodation will be fit for purpose. This risks the housing built for more moderate or low incomes still being constructed at shoebox sizes (view Shelter’s policy briefing for details). In summary, a number of issues in the consultation document are considered to be addressable through market forces, not requiring regulation. There is no assessment of the financial impact felt by homebuyers and occupants if this isn’t true.

Additional burdens for local plan preparation

The focus in this consultation document is about reducing the cost burdens on developers. This is echoed in the definition of viability in the National Planning Policy Framework. There is no discussion about the burdens on local planning authorities and local service providers of not planning new developments to be as sustainable as possible (given the technologies, materials and knowledge available today). One of the biggest risks of the housing standards review is that existing standards like the Code for Sustainable Homes and Secured by Design will be removed but not replaced. The consultation document has an aim that “home buyers and tenants are well served by the housing market and that housing needs are suitably met” (para. 117). However, this is undermined by the document’s proposals, which only cover a portion of the issues addressed in standards like the Code for Sustainable Homes.

Government is proposing to put a huge burden on local authorities to prove why more sustainable design standards should be required in their local area. In the case of security, local authorities would need evidence that justified setting policy on a street-by-street basis (para. 172). In tightly stretched planning services, the overall effect of this burden could be that design standards are abandoned. An holistic standard like the Code for Sustainable Homes is easier for planners to apply. Evidence about local need and viability has always been necessary to require the Code through policy. But that does not mean that planners have a comprehensive evidence base covering the need for and cost of every requirement in the standard. If holistic standards aren’t used, developers are less likely to consider new areas of innovation. The Code drives innovation in the housing market by operating a flexible scoring system and pushing developers to go beyond the bare minimum set by regulation. This will not happen in a system where Building Regulations are the only driver.

Achieving sustainable development

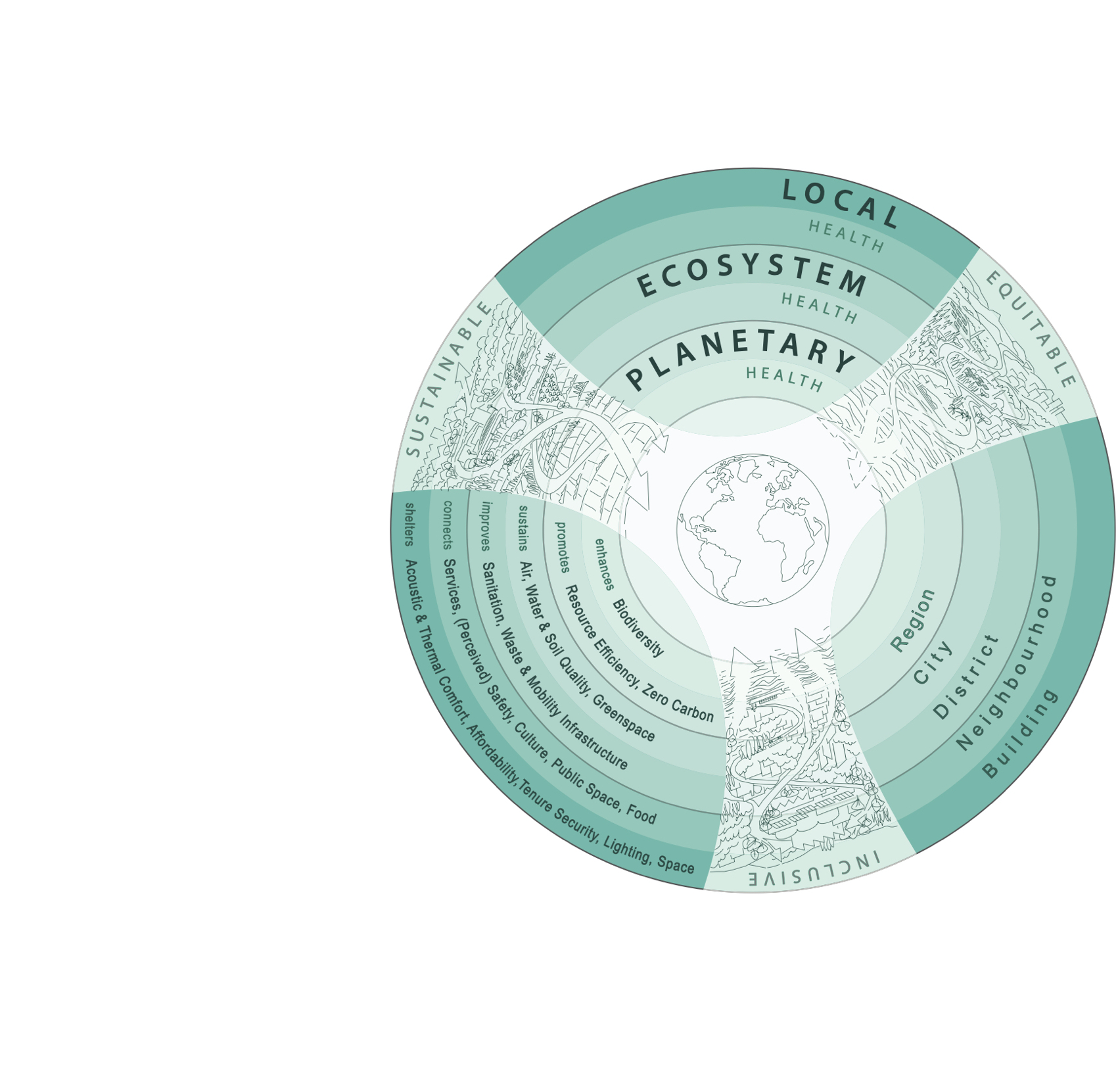

A final thought must be given to the achievement of sustainable development, the principle aim of the planning system. Standards like the Code, Lifetime Homes, Secured by Design and others have been used by planners and planning inspectors (see appeal ref: 12/2169598 ) to gauge whether development proposals are sustainable. Compliance with Building Regulations will not be sufficient. And there will be too many limitations to the potential ‘nationally described set of standards’ for these to be a suitable mechanism (even if they were applied by the local authorities with the time and money to justify their inclusion in local policy). Standards were developed because organisations found gaps in national planning policy and filled them through alternative means. The Housing Standards Review has not found a way of filling these gaps. The whole planning system will suffer if we don’t have the tools to guide unsustainable developments to a better outcome.

These views are wholly my own.