Pineo’s book Healthy Urbanism: Designing and Planning Equitable, Sustainable and Inclusive Places was published in May 2022.

Reviews

“Through the lenses of equity, inclusion and sustainability, Pineo’s ‘healthy urbanism,’ productively builds on existing theory and practice to consider and describe the processes, principles and goals that can support health through urban planning and development.”

—Professor Julian Agyeman, Tufts University, USA

“This treasure-trove book sightsees health and well-being on a journey. Beyond traditional boundaries of urbanism, it voyages by streets, cities, and planetary ecosystems, enhancing synergies between urban disciplines, evolving new approaches to preserve well-being, amplifying opportunities for a healthy and equitable life on a sustainable planet. Masterfully organized, combining social and built environments in a policy-based and historical context, the book anchors in carefully selected case studies, capturing lessons for a new generation of scholars illuminating the potential paths travelled in the pursuit of answers in this invigorating interdisciplinary science.”

—Professor Waleska Teixeira Caiaffa, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil

“This book is an indispensable read for all those concerned about how urban development can support a growing world population, providing equitable opportunities for healthy living within planetary boundaries.”

—Professor Sir Andrew Haines, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK

“Pineo’s examination of healthy urbanism offers a deep dive and systems thinking framework to understanding the social and physical determinants of health. Virus transmission, extreme weather, social isolation and challenges to long standing inequities in how our communities are built and resources are distributed are challenging siloed, single issue approaches to sustainability, well-being and healthy community design. The site-specific examples and case studies brings the research to life and makes this text very readable for people in and outside of public health and urban design disciplines.”

—Sharon Z. Roerty, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, USA

Launch Event

A hybrid (online and in-person) launch event called ‘Urban Health Inside Out’ was held at University College London in July 2022. A panel of speakers discussed their experiences of working to support health through the fields of urban design and planning, public health and property development.

The event was chaired by Prof Yolande Barnes, Chair Bartlett Real Estate Institute, UCL with speakers: Prof Julian Agyeman, Professor of Urban and Environmental Policy and Planning, Tufts University; Kieron Boyle, Chief Executive, Guy’s and St Thomas’ Foundation; Dr Helen Pineo, Associate Professor in Healthy and Sustainable Cities, University College London; and Julia Thrift , Director, Healthier Place-making, TCPA (Town & Country Planning Association).

Recording

Healthy Urbanism book launch event, 7 July 2022, University College London.

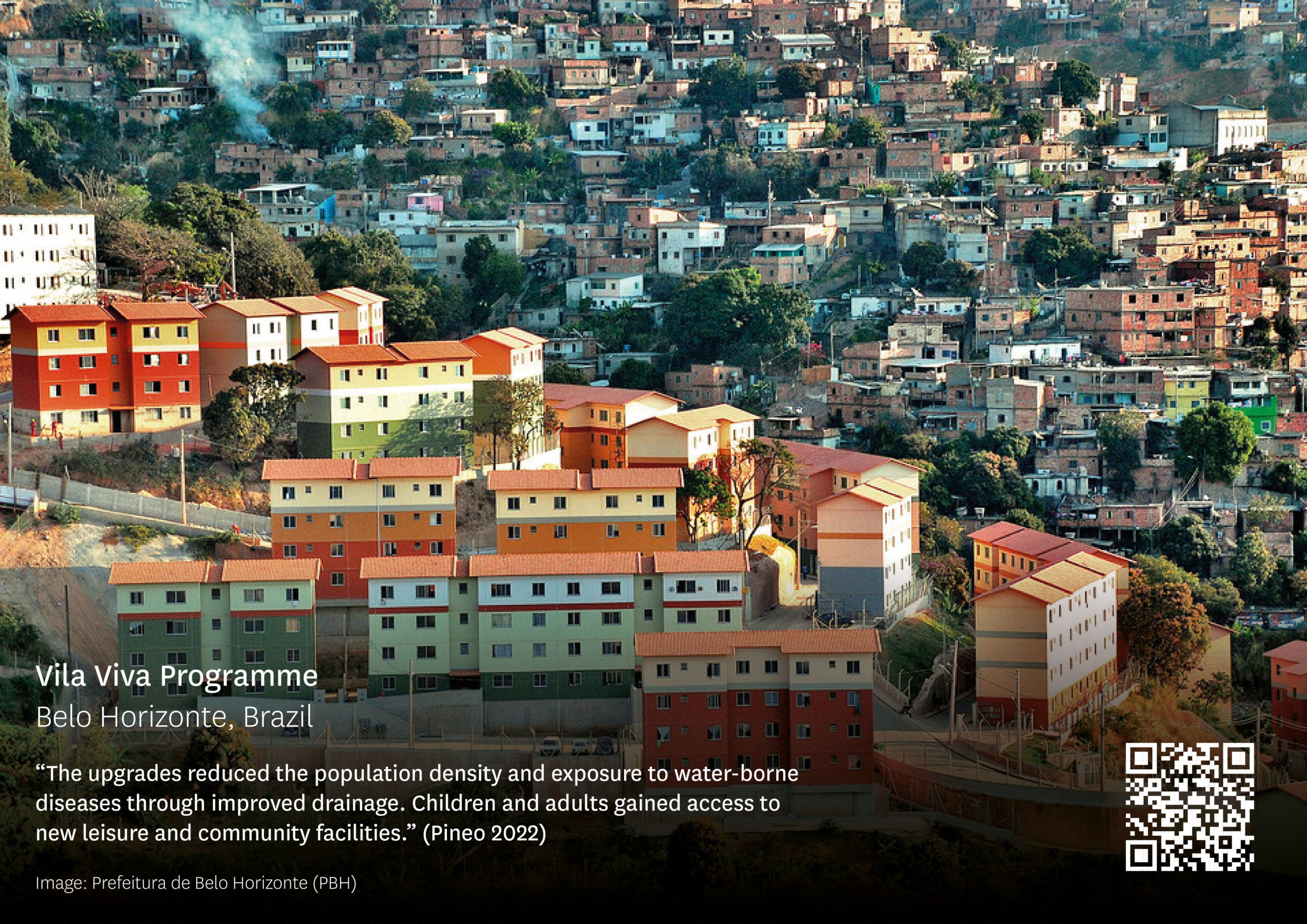

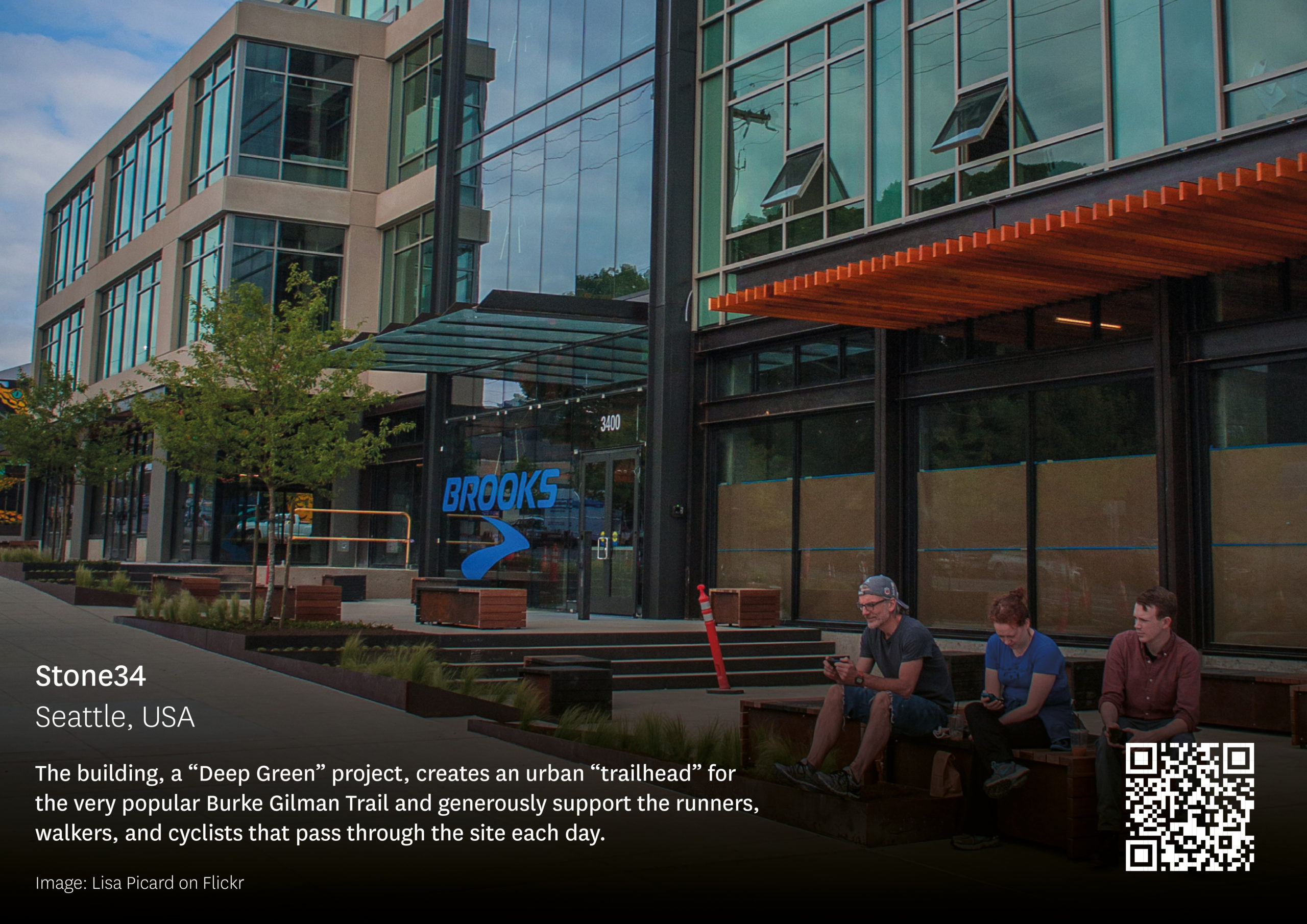

Photo exhibition

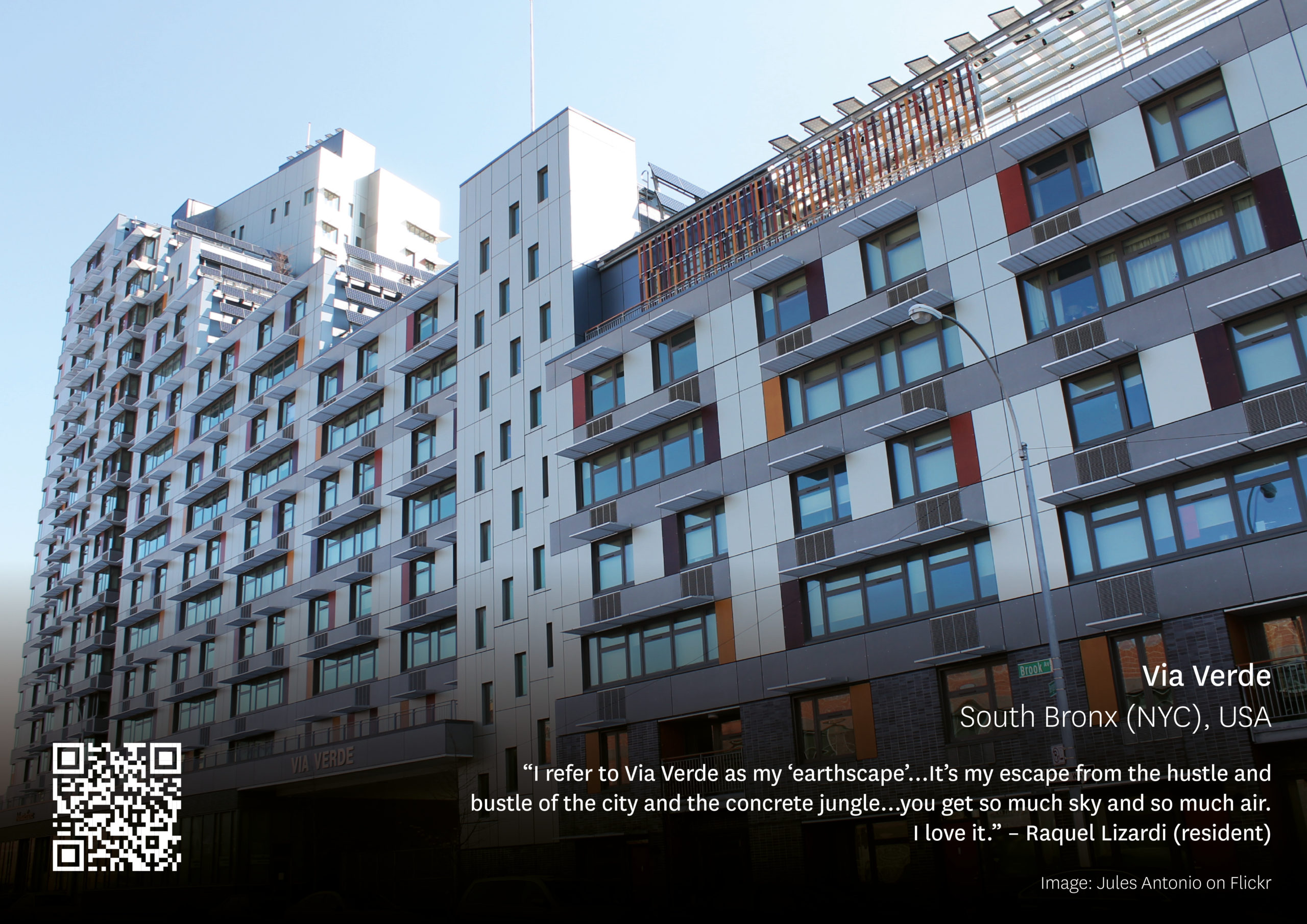

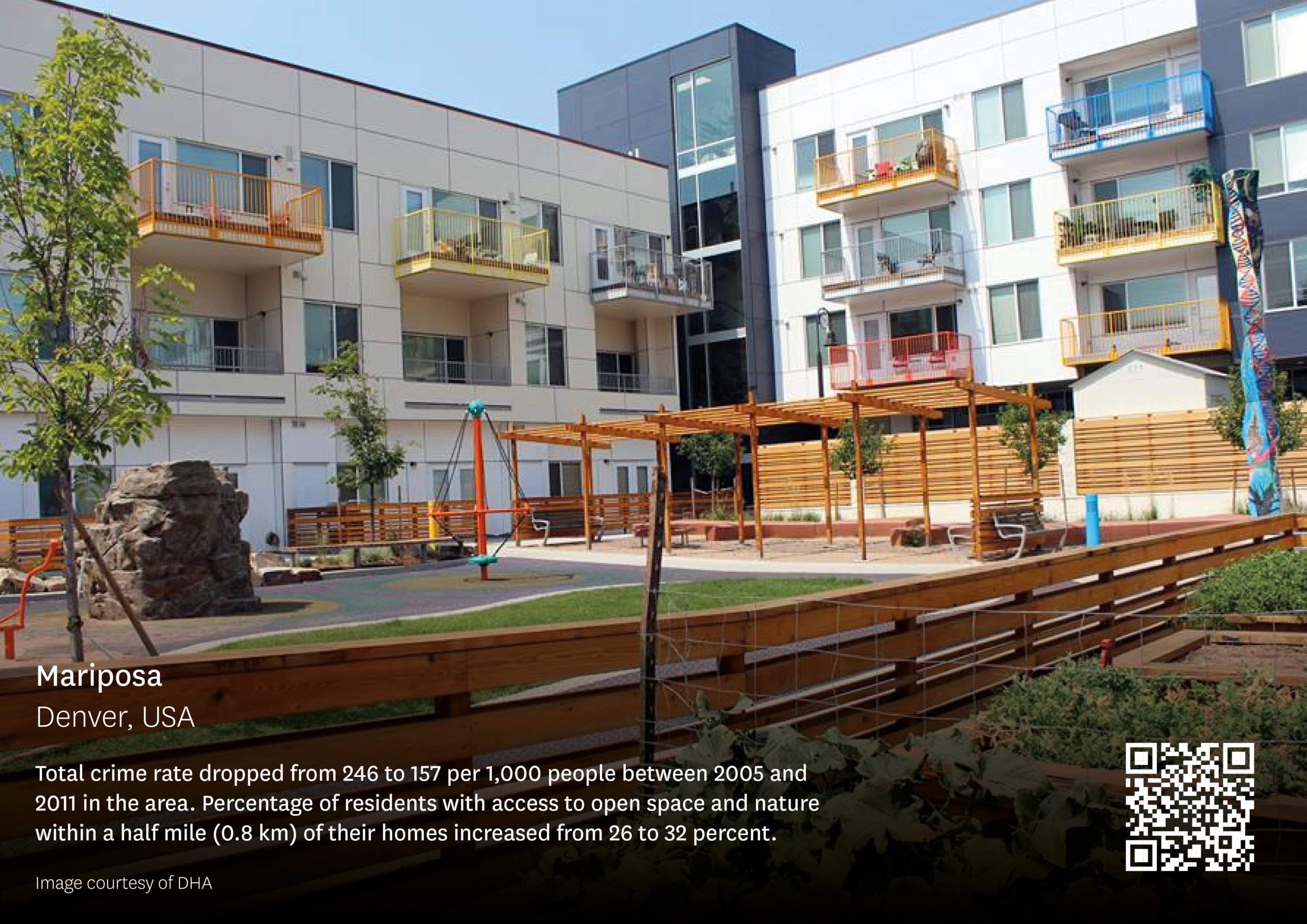

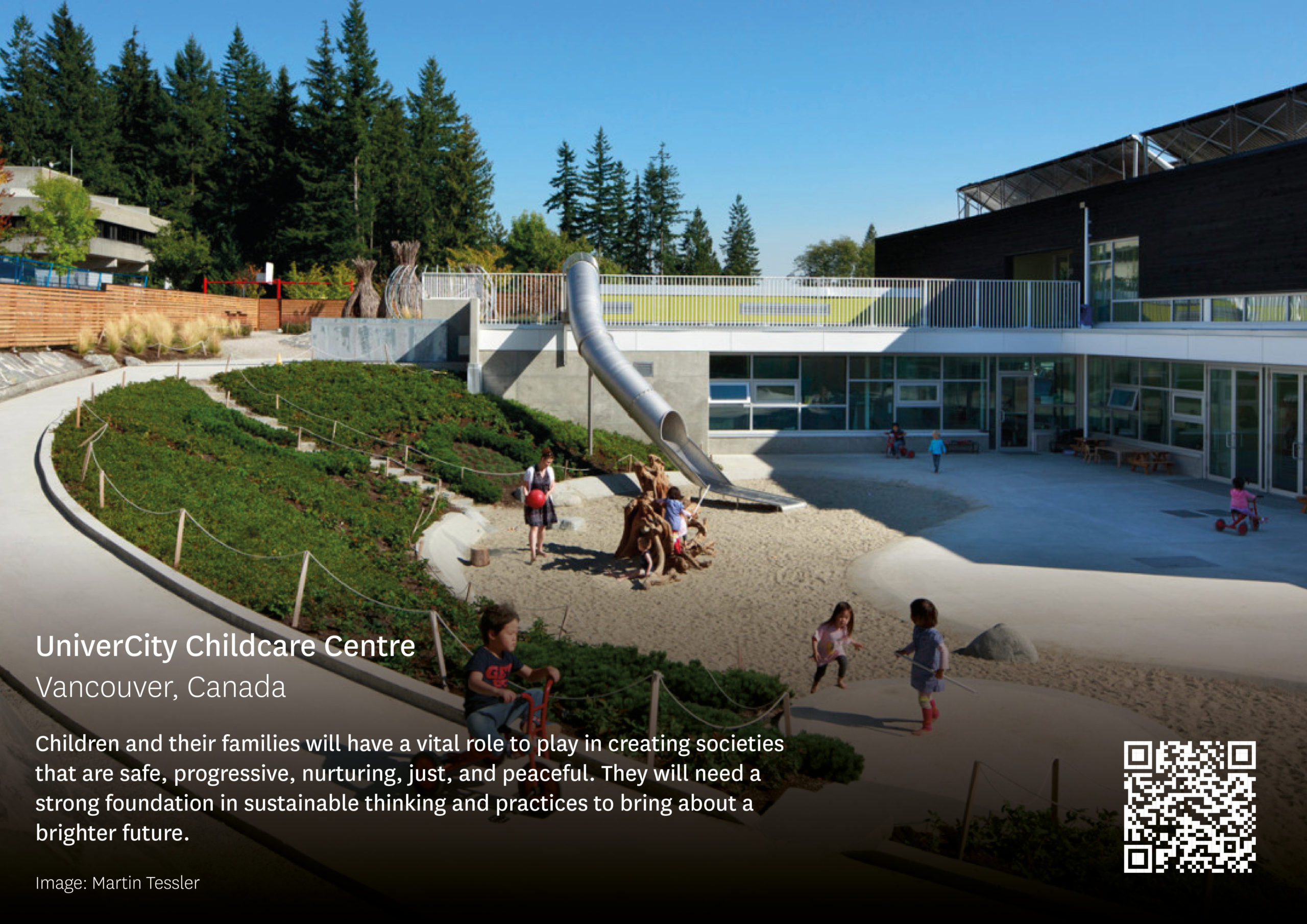

The launch event included a photo exhibition of examples from our healthy urban development case study review and student contributions. A digital version of the photo exhibition is shared below.

About Healthy Urbanism

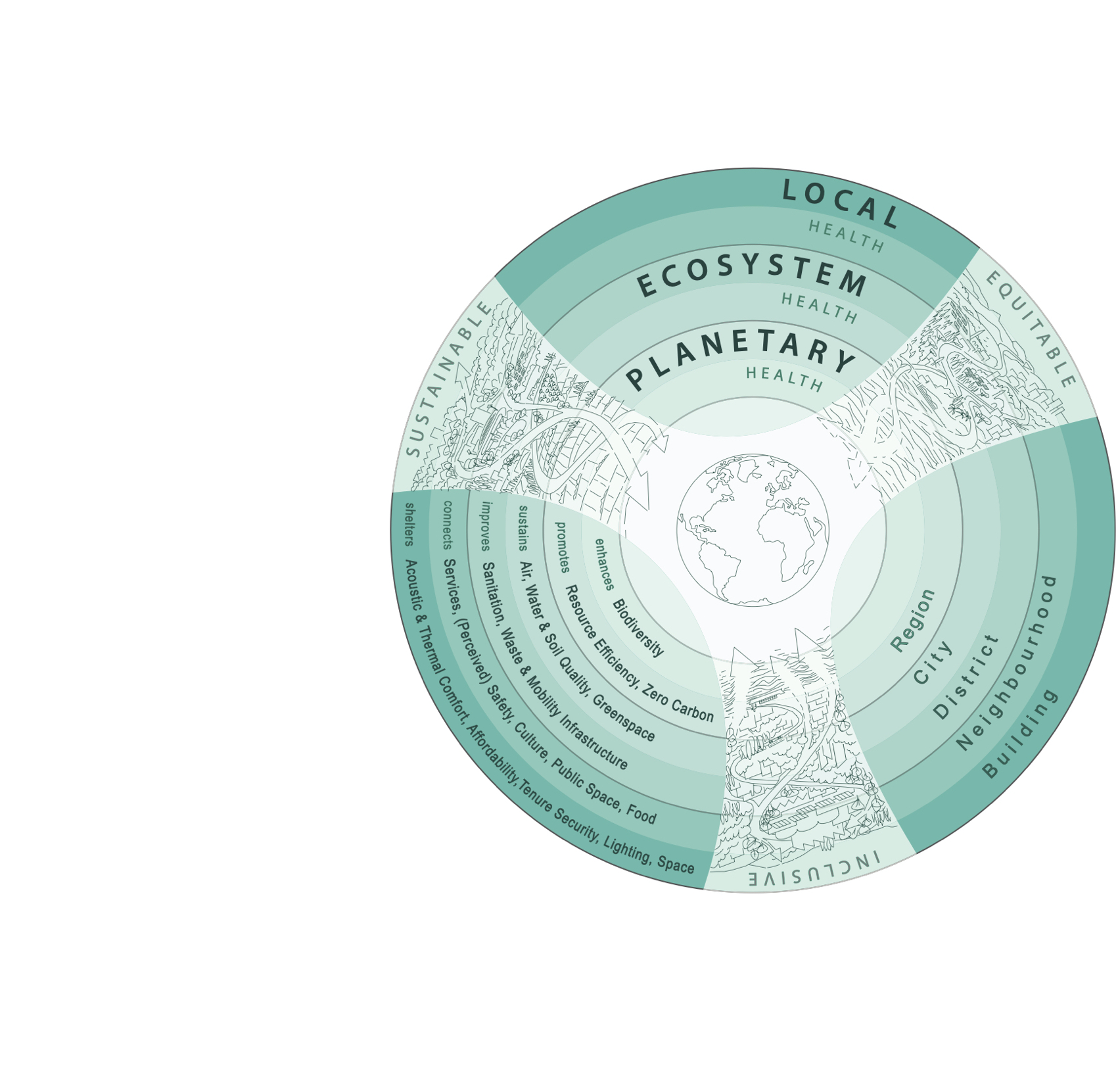

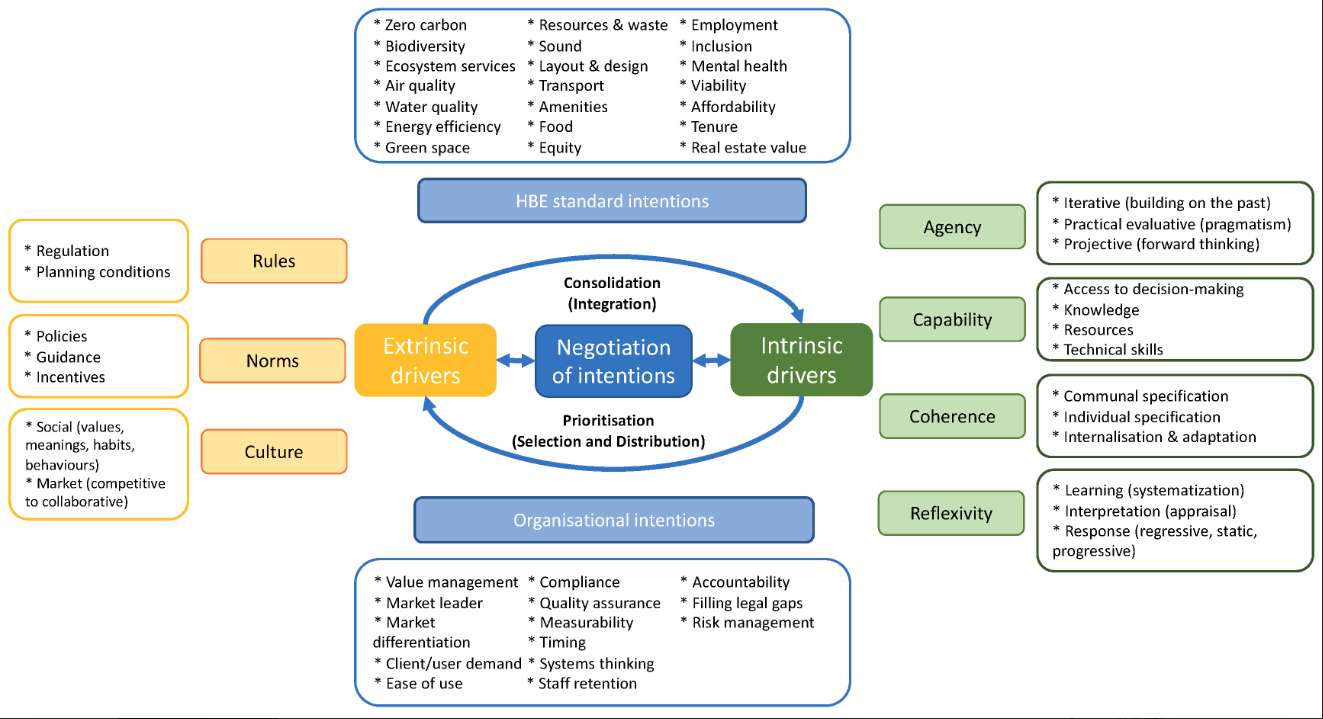

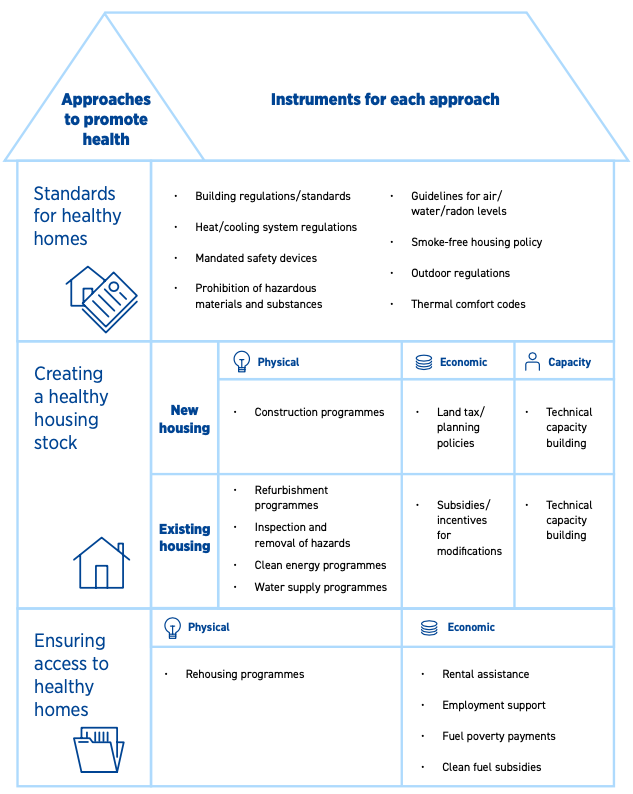

Structured around the THRIVES framework, the book offers a balance of theory and practice, illustrated with case studies. Each of the scales of health impact in THRIVES is examined through a chapter, first using evidence to demonstrate that the status quo of urban design and planning is insufficient to support health and then proposing frameworks and design solutions to overcome this challenge.

The book is a resource for existing professionals and students in built environment and public health professionals. Readers will find sections covering key topics in healthy urbanism, including:

- An overview of health and wellbeing models with key definitions, global trends in urban health and drivers of urbanisation

- Discussion of the shifting priorities for healthy places from ancient cities, social reform, high-rise housing and new urbanism through to 15-minute cities

- Models for conceptualising the built environment’s impact on health and the need for THRIVES

- Deep dives into each scale of health impact in THRIVES, including planetary health, ecosystem health and local health, with in-depth policy and design case studies

- Ways of practising healthy urbanism, covering policy-making, community knowledge, funding healthy places, models of healthy development and monitoring

- Priorities for the future of health urbanism, including disaster prevention and recovery, incremental to transformative urban change, smart cities and framing healthy urbanism.

Endorsements from Professor Julian Agyeman, Professor Waleska Teixeira Caiaffa, Professor Sir Andrew Haines and Sharon Z. Roerty are available on the Springer Nature website.